Once in a Lifetime

Once in a lifetime

Author/Editor: Jennifer J. Lacelle

Date : March 11, 2021

The moment you can walk there’s a pair of skates put on your feet. It’s cold outside, because Quebec City is often chilly with lots of snow, which means it’s time to play ice hockey. Of course, the first pair of skates a child receives isn’t a size ten adult, NHL grade—though parents have hopes and dreams of such.

What children first receive and learn to skate with are a pair of double-bladed skates. That is to say, there’s two blades along the front and two along the back. Then the young skater goes onto the large bladed style before finally obtaining a regular pair.

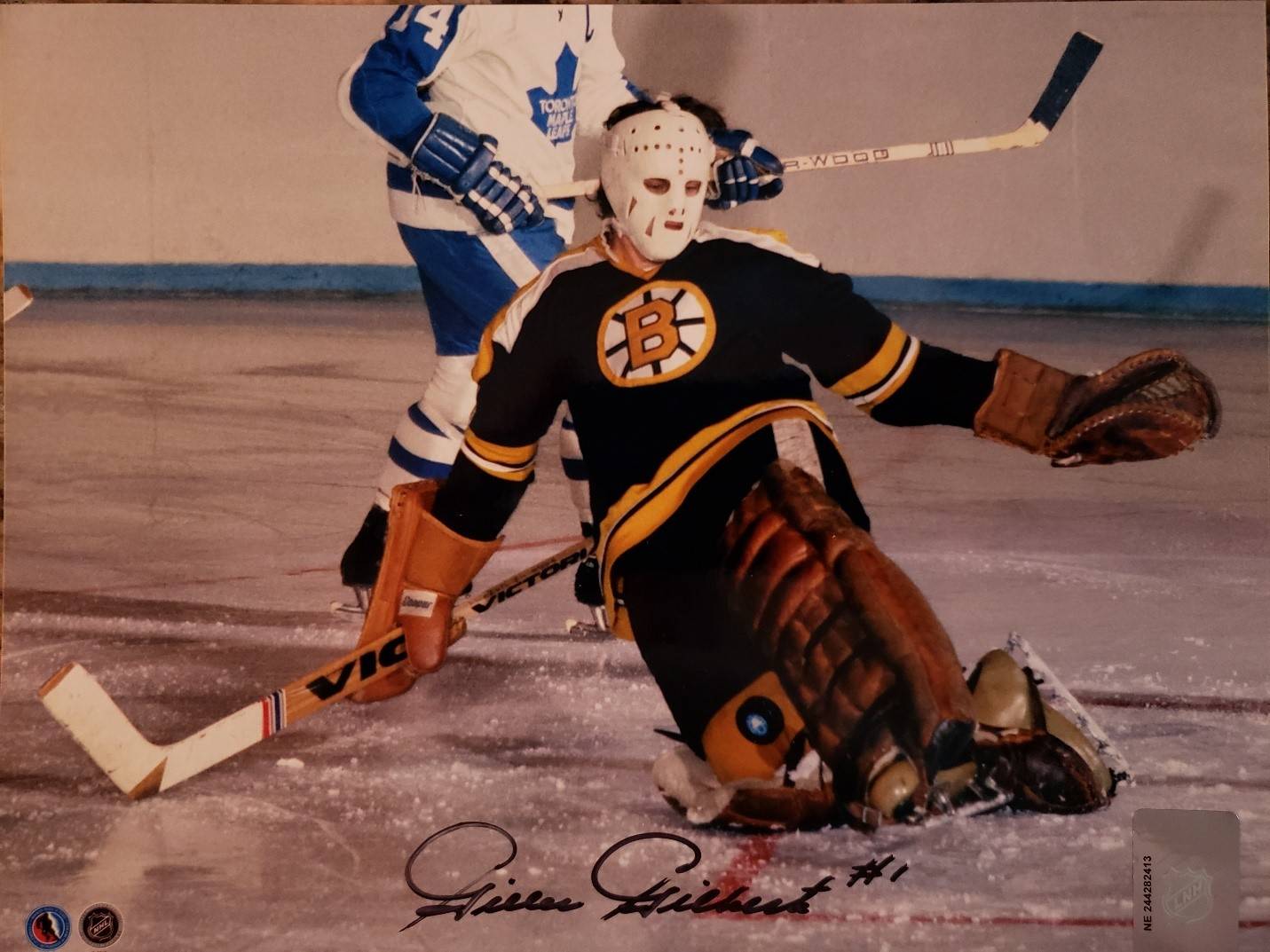

Of course, it’s necessary to build up to regular skates because it’s essential to learn how to slide across the ice first, and ankles need to be strengthened. Gilles Gilbert, one of the top goalies in NHL history, began skating as soon as he started walking. Fortunately for Gilbert, he’s a natural athlete and the pro-baseball leagues wanted to draft him just as much as the NHL did.

He proudly states his daughter, Jennifer, received this athleticism from him and can pick up any sport she tries. His son, Terry, was also a natural on the ice and an excellent goalie, but he chose a different kind of athleticism in the long run and became a firefighter. Funny enough, it was a potential career Gilbert himself would have chosen if hockey hadn’t worked out.

Gilbert’s natural talent and abilities provided him ample opportunity growing up and leading to professional sports. The chance to play major league baseball was openly offered to him around the time he was drafted for hockey.

However, players could spend many years in the minors before ever reaching the majors. A normal baseball player’s career can span well into their forties, which could have been a benefit since in hockey most people retire in their early thirties.

Despite the longer career potential, it didn’t seem nearly as appealing to Gilbert as hockey. Afterall, hockey was built into his DNA. Growing up, his family lived in an apartment across from a church that had ample lighting and space for ball hockey, making it a great resource. He recalls coming home from school for lunch and playing street hockey. A normal day also happened to include a game of hockey after school.

Weekends were also included in this busy schedule and Gilbert recalls playing street hockey down three to four different streets.

It wasn’t just other kids who played though. Gilbert recalls his dad being an excellent goalie and teaching him how to goaltend. His older brother also helped teach him, in fact, he too became a pro-athlete and ended up playing in the American Hockey League.

Even his mom would play street hockey with them. Gilbert began playing in a league at nine years old, however, it was at 13 he knew for sure he wanted to play in the big leagues! It all happened when his brother was playing in the AHL and asked his coach, Boom Boom Geoffrion, if his younger brother could join in place of an injured goalie.

The reason for this wasn’t just Gilbert’s skills, but practicing with only one goalie available is quite difficult. At this point, Gilbert had been playing with people older than him for awhile having done two tournaments in peewee and bantam. “I was always playing not at my level,” he says. “It was pretty strange for a young kid like me to play with the juniors.

All the pictures I’ve got, ‘who is that kid?’ No, I was the goalie.” Although, Geoffrion had initially been concerned about the lack of in insurance but also his age and Gilbert recalls him saying, “my god, this kid is too young.” Gilbert was thankful his dad was there and signed papers stating that the team wasn’t responsible if something did happen to him. This solidified his dream to play in the NHL and he continued to progress and develop his skills. He went on to play in the Juniors in Quebec before moving on to London, Ontario.

Thatshift was a difficult time for Gilbert, not only was he young and away from home but he was the only French speaking person on the team and hadn’t learned English yet. Not only that, but he was replacing a former goalie.

This led him to feeling ostracised among the team. Because he didn’t speak English, Gilbert didn’t know what was going on, and he says there were moments when he would enter the showers and everyone else would just leave. Furthermore, he was unable to obtain rides unless he stayed into the wee hours of the morning just to get a ride from the trainer.

Despite living with three other players, they “wouldn’t let him in the car” and left him to walk a mile to the arena or catch a bus.

“No one spoke to me,” Gilbert says. “Then after practice when it’s 3:30 a.m., you don’t feel like hanging up the equipment [to obtain a ride home]. I don’t wish that any anybody. It was tough.”

In fact, partway through the first season he called home and told his dad he couldn’t “stand the situation” anymore. He even looked up the price of a ticket from London to Quebec City and asked his dad for the money ($85) when he called, but his father told him no. “I want you to play there,” Gilbert recalls his father telling him.

However, the situation didn’t improve and when they were playing a game in Quebec City a few weeks later, Gilbert had packed all his bags and brought them with him. After the game, his father asked where he was going and Gilbert said he was going home with them. However, his dad once again told him no.

“You’re finishing. It’s your last year in junior, and having a great season, you’ll have a much better chance to be in the NHL,” Gilbert recalls his dad saying. Reflecting on it, Gilbert says, “thank God I said ‘okay, I’m going to go back with the team.’ So, we lead the playoffs and all of a sudden everyone wants to pick me up and drop me off.”

Finally! In 1969, Gilbert was drafted to play in the pros at the age of twenty. He was the third pick and was feeling great! Though, it initially didn’t go as planned. While he wanted to play in the NHL, he wasn’t too impressed with the contract as it wasn’t very much of a paycheck.

They told him if he didn’t sign it then he would be on the next bus back to Quebec City, so he signed on. Thereafter, they told Gilbert he would play in the minors for one month. During those four weeks he had a great time but awaited their call patiently. True to their word, they called after a month and but he only ended up playing two games.

The morning after his flight, he called the coach and told him not to search for him, that he was in Cleveland and wanted to play. He also told him that it was ridiculous to be waiting a month without playing.

“They could have kicked me out for that,” Gilbert says. He joined a practice there only to be told they were playing a game that night and he was invited. Gilbert ended up playing because their best goalie had been injured, he actually showed up in crutches with a broken ankle.

After they won the game, Gilbert’s coach showed up and stood next to him but never spoke to him. Gilberts says, “he was mad.”

Usually, Gilbert notes, when people are sent from NHL to the minors it’s because of an injury. While that wasn’t the case for him, the coaches were lying and said that was the reason for his arrival in Cleveland.

Gilbert played five games with them before returning to Minneapolis though he still didn’t play very much upon his return. “They should have left me there to play the rest of the season,” he says. In 1973, he was traded to the Boston Bruins, where he would spend the next seven years of his total 14-year career.

Gilbert earned a stellar record of 17 consecutive wins and it remains unbroken, though he says someday it will be. His overall SV% is .883—which is absolutely remarkable for a goalie’s career.

After his retirement in 1983 he tried several different jobs but went back gone back to his roots in hockey. He’s spent the last 35 years working for Canadian Hockey Enterprises as their public relations liaison; part of that includes handing out shirts, speaking to players and giving the teams their trophies.

“I’m still in hockey, that’s where I belong.”

Gilbert also had the opportunity to play in the NHL Hockey Legends: 30 games in 30 days, two days off, and repeat, for five months.

It was strenuous but he had a blast playing these games. He strongly credits his wife, Diane, for being resilient throughout their 47 years of marriage, stating she often raised the kids alone since he was away constantly. “She was patient all these years,” Gilbert says before laughing.

“I’m keeping her, I’m not trading her, no way! Only goalies get traded.” iinta believes in fair trade for all works of art, products, services and sales. As such, when purchasing authentic pieces from iinta you are paying the athletes and artists